Navigating Federal Grants: A Professor's Guide to Drone Acquisition and the American Security Drone Act

Using federal grant money for drone research? This essential guide breaks down the critical requirements of FAR Part 40 and Clause 52.240-1, helping university professors understand the new restrictions on purchasing and using drones from covered foreign entities, including advice on existing DJI equipment.

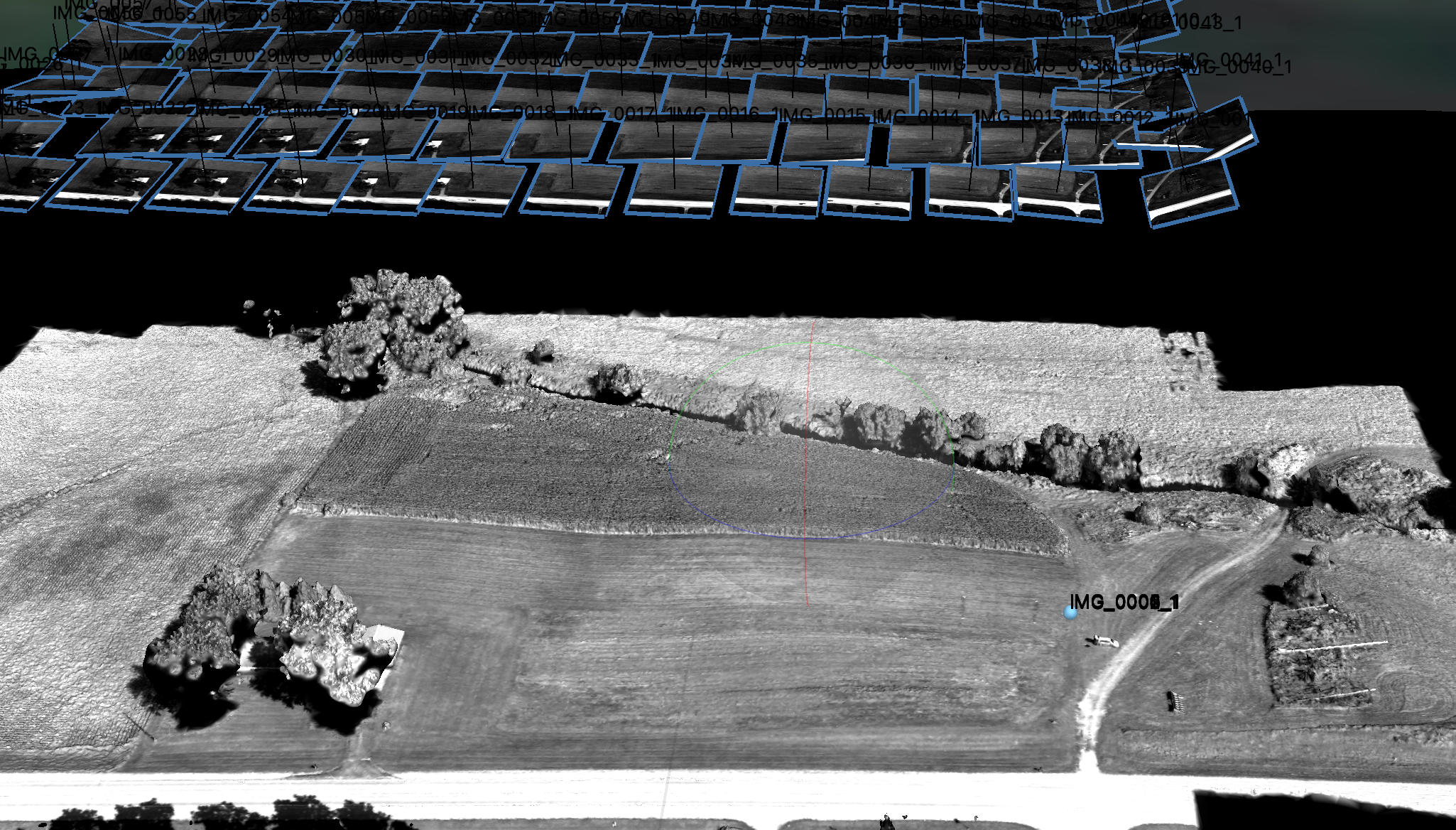

RedEdge-P RGB Composite of an Iowa bean field

The intersection of groundbreaking research and cutting-edge technology often finds its sweet spot within the halls of academia. Federal grants are powerful engines for this innovation, enabling you to acquire the tools necessary to push the boundaries of knowledge. For many of you, this includes the burgeoning field of drone technology – unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) that offer unparalleled capabilities for data collection, environmental monitoring, infrastructure inspection, and so much more.

However, just as the skies are becoming more regulated for drones, so too are the regulations surrounding their acquisition with federal funds. A critical piece of legislation you need to be aware of is the American Security Drone Act of 2023, implemented through the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR). If you're planning to use federal grant money to purchase drones, understanding FAR Part 40 - Information Security and Supply Chain Security and specifically FAR Clause 52.240-1 - Prohibition on Unmanned Aircraft Systems Manufactured or Assembled by American Security Drone Act-Covered Foreign Entities is not just good practice, it's a mandatory requirement.

Let’s break down what this means for your research and procurement processes.

The Heart of the Matter: Why These Regulations Exist

The core intent behind these regulations is national security. In an increasingly interconnected world, the supply chain of technology, especially sensitive technology like drones, has become a significant concern. The U.S. government aims to prevent the use of federal funds to procure drones that pose potential risks to information security or national defense due to their origin.

Delving into FAR Part 40: Information Security and Supply Chain Security

FAR Part 40 is a relatively new addition to the Federal Acquisition Regulation, establishing a dedicated section for "Information Security and Supply Chain Security." While broad in its scope, its primary purpose is to address the risks associated with information and communication technology (ICT) and other items and services procured by the government.

For professors, this means that when you're using federal grant money, the government isn't just concerned about the drone's specifications or its cost; it's deeply interested in where that drone came from and who manufactured or assembled it. This part lays the groundwork for ensuring that items purchased with federal funds do not introduce vulnerabilities into federal systems or operations. Even if your university is not a federal agency, as a recipient of federal funds, you are generally bound by these procurement requirements.

The Specifics: FAR Clause 52.240-1 and the "Covered Foreign Entities"

This is where the rubber meets the road for your drone purchases. FAR Clause 52.240-1 is titled "Prohibition on Unmanned Aircraft Systems Manufactured or Assembled by American Security Drone Act-Covered Foreign Entities." Its purpose is straightforward: it prohibits the use of federal funds to procure certain drones.

What does "Covered Foreign Entity" mean? The Act and subsequent FAR clause define specific foreign entities (and their subsidiaries or affiliates) whose drones are deemed high-risk. While the specific list of entities can evolve, the spirit of the law is to exclude manufacturers and assemblers tied to countries identified as posing national security threats. Historically, this has primarily focused on entities associated with the People's Republic of China, among others. DJI, being a prominent Chinese manufacturer, is a key entity typically encompassed by such prohibitions due to its origin.

Key Implications for Your Research:

Due Diligence is Paramount: Before you even draft your purchase order, you must conduct thorough due diligence on the drone manufacturer and assembler. This goes beyond checking technical specifications or price. You need to verify that the drone you intend to purchase is not manufactured or assembled by a "covered foreign entity."

Verify the Supply Chain: The clause doesn't just apply to the primary manufacturer; it also extends to the assembly process. A drone might be designed by a compliant company but assembled using components or by entities that fall under the prohibition. Understanding the full supply chain of your chosen UAS is crucial.

Certification and Representation: When you make a purchase using federal funds, your institution will likely be required to make representations or certifications that the procured drone complies with this clause. Falsely certifying compliance, even inadvertently, can have significant consequences.

Can I Use My Existing DJI Drones on New Federally Funded Projects?

This is a frequently asked question, and the answer is nuanced. While FAR Clause 52.240-1 primarily targets new procurements of drones with federal funds, the spirit and intent of the broader legislation often extend to the use of prohibited equipment in connection with federal projects, especially where data security and national security are concerns.

Here’s what you need to consider:

The "Procurement" vs. "Use" Distinction: The clause explicitly states "prohibition on Unmanned Aircraft Systems Manufactured or Assembled by American Security Drone Act-Covered Foreign Entities." The key word here is "manufactured or assembled," which points to the acquisition phase. If your DJI drone was purchased before the effective date of these prohibitions (November 12, 2024, for FAR 52.240-1) and without federal grant money subject to these specific restrictions, then the clause itself does not directly prohibit its prior acquisition.

Agency-Specific Requirements: This is where it gets critical. While the FAR clause governs procurement, individual federal agencies (e.g., DoD, NSF, NIH) that issue grants may have their own terms and conditions that go beyond the FAR. Many agencies have implemented policies, sometimes predating the FAR clause, that restrict or prohibit the use of drones from certain foreign entities in projects they fund, regardless of when or how the drone was originally acquired. These restrictions are often driven by concerns about data exfiltration, cybersecurity, and supply chain integrity.

Risk Assessment and Data Security: Even if an agency's terms don't explicitly forbid the use of your DJI drone, you should seriously consider the data security implications. Are you collecting sensitive data? Where is that data stored and transmitted? Could the drone's software or hardware create vulnerabilities? Many universities have their own policies regarding the use of "covered" drones due to these risks.

Indirect Costs and Allocability: If you plan to "charge" the use of a previously purchased DJI drone (e.g., through an internal use charge or as part of facilities & administrative costs) to a new federal grant, you might face challenges proving that such costs are "allocable" to the project if the agency prohibits the use of such equipment.

The Bottom Line on Existing DJI Drones:

It is highly advisable to assume caution. Before using any previously purchased DJI drone (or any drone from a "covered foreign entity") on a new federally funded project:

Review the specific terms and conditions of your federal grant award. Look for any clauses or directives related to drone use, data security, or prohibited equipment.

Consult your university's Sponsored Programs or Research Compliance Office. They will have the most up-to-date information on institutional policies and specific agency interpretations.

Be prepared to justify the use, or better yet, plan for compliant alternatives. In many cases, the safest and most compliant approach for new federal projects will be to acquire or use drones from approved manufacturers.

Practical Steps for Professors:

Consult Your Grant/Sponsored Programs Office: This is your first and most important step. Your university's grant or sponsored programs office will be the most knowledgeable about specific institutional policies and procedures for complying with federal regulations. They can provide guidance on documentation, verification processes, and approved vendor lists.

Engage with Procurement: Work closely with your university's procurement department. They are equipped to handle supplier vetting and can help ensure that any drone purchase aligns with FAR requirements.

Demand Transparency from Vendors: When sourcing drones, explicitly ask potential vendors about their compliance with the American Security Drone Act and FAR 52.240-1. Request documentation detailing the manufacturing and assembly origins of their products.

Stay Informed: The landscape of federal regulations can change. Keep an eye on updates from your university's compliance offices and federal acquisition resources.

Looking Ahead

These regulations, while adding a layer of complexity to the procurement process, are designed to safeguard national interests. For university professors, they underscore the importance of not just what you buy, but where it comes from, especially when using taxpayer dollars. By being proactive and working closely with your university's support infrastructure, you can continue to acquire cutting-edge drone technology for your research while remaining fully compliant with federal guidelines.

Happy researching, and may your drone flights be secure and successful!

Important Disclaimer

This blog post is intended for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute legal, regulatory, or procurement advice.

The information provided here is based on publicly available Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) documents (Part 40 and Clause 52.240-1) and general interpretations of the American Security Drone Act of 2023. Federal regulations are complex, frequently updated, and subject to interpretation by specific granting agencies (e.g., NSF, NIH, DoD) and university compliance offices.

You must not rely solely on this information for making decisions regarding the purchase or use of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (drones) with federal funds.

Always Consult: You should always consult with your university’s Sponsored Programs Office, Research Compliance Office, and/or legal counsel to ensure full compliance with the specific terms and conditions of your grant award and institutional policies.

No Attorney-Client Relationship: Reading this post does not create an attorney-client relationship. Multispectral Systems LLC is not responsible for any actions taken or not taken based on the content herein.

Processing RedEdge-P Data

Watch this video for step-by-step instructions on processing RedEdge-P data.

This video shows one possible workflow for processing RedEdge-P data in Metashape Professional. The end of the video includes some data analysis in QGIS.

Choosing the Right Multispectral Sensor for Agriculture Research - AgEagle Camera Review

Multispectral sensor comparisons from the field.

This blog was authored by Gary Nijak of AerialPlot, published on August 25, 2025. The original LinkedIn post can be found here.

The AgEagle Altum-PT, RedEdge P Dual, and the RedEdge MX Dual on a sunny Minnesota morning getting ready to be put in the sky!

Field-Tested Camera Comparison: Altum-PT vs. RedEdge P Dual vs. RedEdge MX Dual

It’s not often that I have all of AgEagle Aerial Systems Inc.'s cameras in the office at the same time. Most of the time, they’re scattered across different deployments and projects. So, when the opportunity came up, I decided to conduct a side-by-side test that I hadn’t done before.

I flew the AgEagle Altum-PT, RedEdge P Dual, and RedEdge MX Dual over a small soybean plot at 200 ft (about 60 m) AGL, with 80% sidelap and a slower flight speed that pushed the frontal overlap closer to 90–95%. The site was flat, so there was no need for terrain correction.

The goal: to create an apples-to-apples comparison of these sensors under identical conditions.

Measured GSD vs. Published Specs

These numbers were what they were - no surprises here. (Note - I have included updated GSDs for two of the cameras. To generate the improved workflow numbers vs the published workflow, I followed all of the steps but I cleaned the point cloud in Agisoft and removed weak matches to improve the overall accuracy of the orthomosaic. This significantly improved the GSD of the cameras)

The Altum-PT should have produced ~1.25 cm/pixel at 200 ft, but my data came in at 2.66 cm/pixel using the published workflow. This discrepancy was most likely due to poor matches in Agisoft so I cleaned the point cloud, and then rebuilt the orthomosaic. This resulted in a GSD of 1.26 cm/pixel. Pretty much as advertised.

The RedEdge P Dual showed a similar story. Published specs suggest ~2.0 cm/pixel, but I measured 3.9 cm/pixel. Again, workflow settings can easily explain the difference so I reran using an improved workflow and got 2.06 cm/pixel, again, spot on.

The RedEdge MX Dual, on the other hand, matched expectations at ~4.27 cm/pixel, consistent with its published ~4.0 cm/pixel resolution at this altitude. I didn't bother to redo this stitch because the resolution was right as advertised.

Of particular note, there are lots of features in photogrammetry software such as Agisoft and Pix4D. Many times it can be straightforward to follow published workflows but there are a lot of considerations when trying to collect analytical quality data from multispectral drones and end up with a usable product. User caution is advised!

One other note on processing - there are known issues in Agisoft Metashape and Pix4DFields with the RedEdge P Dual that are not yet resolved (as of 8/15/2025). So keep an eye out if you are using this camera for artifacts that exist in the processing step.

Third note on processing - there is a lot that goes on under the hood for the panchromatic sharpening in both the Altum PT and the RedEdge P systems. Make sure, if it matters, you understand some of those intricacies because they can be important.

Performance Insights

Altum-PT

The Altum-PT remains the top performer in image quality. However, its massive data footprint makes it a challenge to manage. For small research plots, the volume is manageable, but in commercial operations, we’ve quickly burned through multiple 20 TB hard drives just trying to keep pace with the data storage and processing requirements. It does occasionally suffer from the missing photo but our high overlap situations don't seem to be impacted.

RedEdge P Dual

The P Dual is where things get interesting. We recently added the Blue camera to our existing Red setup, and that upgrade introduced some hardware and technical quirks that we’re still working through. Before that change, the single RedEdge P (Red) camera had been solid and reliable, and I expect the dual system will reach that same level once these issues are fully resolved.

RedEdge MX Dual

The MX Dual has been our workhorse for years. While its imagery doesn’t match the newer sensors in terms of raw resolution or quality, it’s reliable and consistent. And, to be clear, this is a 10-band system, so it’s not exactly low-complexity — but compared to the P and Altum platforms, it’s still more straightforward to manage in day-to-day workflows.

Unfortunately, the MX Dual is now end-of-life, which means no more support or repairs. That’s going to be a challenge for teams still relying on it as their primary multispectral solution.

Choosing the Right Sensor for Research

When it comes to research applications, the choice of sensor depends heavily on the question you’re trying to answer.

Altum-PT – Its thermal band gives it unique capabilities for research involving canopy temperature, crop stress, or water-use studies. However, its limited number of spectral bands makes it less ideal for building or validating broad-spectrum satellite models that require higher spectral resolution.

RedEdge MX Dual – Even though it’s now end-of-life, the MX Dual remains a versatile, reliable choice for most standard multispectral work. Its 10 bands cover a solid range of wavelengths, making it suitable for many vegetation indices and zone-specific profiling tasks without overcomplicating data management.

RedEdge P Dual – This system promises higher resolution and greater scalability for larger areas, but it still doesn’t quite hit leaf-level detail at typical flight altitudes. Additionally, while it’s strong for applications like spectral profiling and precision agriculture, it’s less ideal for architecture or structural questions where ultra-high-resolution imagery is needed.

In short:

For thermal research, Altum-PT stands out.

For general multispectral research, MX Dual often works best—when you can still get it.

For scalable spectral profiling, the P Dual is promising but still not fully optimized for certain advanced analytics.

Key Takeaways

Data Management Is Critical – Higher resolution and more bands mean exponentially larger datasets. At commercial scale, storage, processing power, and workflow efficiency quickly become pain points.

Real-World vs. Spec Sheets – Published numbers are a useful benchmark, but your processing choices and field conditions can have a huge impact on final outputs.

Reliability Matters – Raw performance is important, but when you’re flying high-volume missions, a stable, predictable system often outweighs marginal improvements in image quality.

Final Thoughts

This was a small-area test, so efficiency at scale wasn’t the focus. Even so, it provided valuable insights into how these cameras handle data capture, processing workflows, and operational reliability.

For now, the Altum-PT remains our niche for projects demanding the highest resolution and spectral range, though we’re mindful of the storage and processing demands and can only afford so many of these things with the >$15K price tag. The P Dual shows promise once its dual-band reliability issues are fully resolved, but again has a fairly high price point for the average researcher and may drive people towards a more integrated system such as the DJI Mavic 3 Multispec if it remains available. And the MX Dual — while aging — continues to prove that consistency and simplicity can still win the day.

For other questions, contact the folks at AgEagle. I'm not a sales person for them, but I have used their cameras a lot. I'm open to other systems, this is just the one we've used to data. But we're always testing others!